Colour mark for pharmaceutical products: the purple threshold

The General Court, in denying that the Applicant’s colour sign would be eligible for trade mark registration, has provided further guidance on the probative value of surveys used by trade mark applicants to prove that distinctive character of a sign has been acquired through use of the mark.

Background

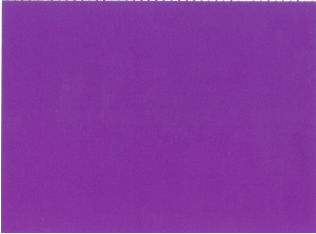

In 2015, a pharmaceutical company (the “Applicant”) filed an application at the EUIPO for the registration of an EU trade mark consisting of the following colour sign:

The sign was described as a colour mark identified as “Purple – Pantone: 2587C”. Registration was sought for inhalers and pharmaceutical preparations for the treatment of asthma.

The EUIPO rejected the application on the grounds that the proposed mark lacked inherent distinctiveness. The EUIPO examiner’s view was that it would be perceived by the relevant public as an indication of certain characteristics: at least in some Member States, inhalers marketed in a violet/purple colour contain specific combinations of medical products designed to relieve specific symptoms.

The Board of Appeal fully upheld the first instance decision, holding that the mark applied for was descriptive in nature. It is established that applicators for asthma medicines are designed in different colours. The choice of colour thereof shows a certain reference to the active ingredient contained and to the purposes and characteristics of the drug.

The Applicant further appealed to the EU General Court (Case T-187/19)[1] which, in confirming the decisions of the lower courts, provided guidance on the probative value of survey evidence submitted by trade mark applicants to support acquired distinctiveness among the relevant public.

The General Court’s decision

Inherent distinctiveness

The Court provided a reminder that, as regards the registration of a colour which is not spatially defined, it is in the public’s interest not to unduly restrict the availability of colours for use by others.

With regard to the inhalers, according to the Court, even if there were not any legislative or regulatory provisions imposing a specific colour, the good practice guide established by the European Medicines Agency recommends that the choice of colour should be considered during product design to ensure that it does not introduce any risk of confusion with other established products where informally agreed conventions exist. In the Court’s view the goods covered by the trade mark application did not escape such guidelines and practice.

Acquired distinctiveness

The lack of inherent distinctive character of a sign does not preclude it from being registered as an EU trade mark when it is shown that it has acquired distinctive character through use throughout the EU.

In assessing the probative value of the survey evidence, the Court held that the following criteria should be considered:

- the sample size and reach (both in terms of relevant public and of number of countries within the EU), which here was considered too low;

- the objective circumstances in which the mark at issue is presented in the surveys: in this case, target consumers were shown only one image representing a shade of the colour purple and therefore were not placed in a position to choose from among several images the one that could be spontaneously associated with the Applicant; and

- the consistency among surveys as to the colour mark; in the Court’s view, the majority of the examined surveys did not specify the Pantone Code of the colour purple or showed shades of purple changing from one survey to another.

The take-away message

This case exposes the threshold that trade mark applicants may face when seeking to register a colour as an EU trade mark. If relying on survey evidence to establish characteristics such as acquired distinctiveness, it is essential to ensure the quality of such evidence meets the required thresholds.

Based on the Court’s findings, here are some practical considerations that brand owners should consider when preparing survey evidence:

- ensure that the territorial and target coverage of the survey is wide enough to support findings such as acquired distinctiveness throughout the EU and the relevant public;

- if the focus of the survey is in relation to a particular colour mark, make sure the relevant shade used is consistent among surveys; it would be prudent to include a specific reference to a known colour coding system, such as a pantone number; and

- if looking to demonstrate whether the relevant public would be able to associate a shade of colour with a specific product or brand, if possible, include alternative colour options for the respondents to review.