Morality in brand management

Laws in the UK and EU, and elsewhere worldwide, exclude from registration trade marks that are contrary to public policy or to accepted principles of morality. These provisions are aimed at balancing the rights of businesses to freely employ words and images they feel will best enhance the sales of their goods or services, and to protect these as trade marks, against the right of the public not to encounter disturbing, abusive, insulting and even threatening trade marks. The rules are intentionally broad to avoid granting a monopoly to brands that would be perceived by the relevant public as going directly against the basic moral norms of society.

The application of these provisions is not limited by the principle of freedom of expression since the refusal to register only means that the sign is not granted protection under trade mark law and does not stop the sign from being used — even in business.

Readers will not be surprised to hear that freedom of expression still hits up against the morality provisions. Leading cases have therefore stated that “registration should be refused only where it is justified by a pressing social need and is proportionate to the legitimate aim pursued. Furthermore, any real doubt as to the applicability of the objection should be resolved by upholding the right to freedom of expression and thus by permitting the registration” (Woodman v French Connection Ltd [2007] E.T.M.R. 8). In that case, a trade mark application had been filed for ‘FCUK’, which was derived from the name of the UK subsidiary French Connection UK. Evidence existed that the owner had played upon the closeness of the acronym to the word ‘fuck’ in advertising when creating the brand name, but this was not enough for the UK Intellectual Property Office (“UKIPO”) to refuse registration.

In another well-known UK case, which concerned the trade mark application for ‘TINY PENIS’ and clothing, Simon Thorley Q.C. cautioned that the fact that a section of the public would find the mark offensive may invoke the refusal of registration, but mere distaste is not enough unless the trade mark would “justifiably cause outrage“. In that case, the UKIPO refused registration for the trade mark ‘TINY PENIS’. The decision has since been heavily criticised.

To provide some context on the scope of these provisions, we review two recent UK and EU trade mark decisions and consider their impact on brand management.

The Court of Justice for the European Union (“CJEU”) recently considered the impact of these principles in relation to an EU trade mark application for ‘Fack Ju Göhte’ which was filed by Constantin Film Produktion GmbH (“Constantin”) in 2015 for various goods and services (C-240/18 P; Constantin Film Produktion GmbH v EUIPO, 27 February 2020). Constantin produced the well-known German comedy film ‘Fack Ju Göhte’ in 2013 and sequels in 2015 and 2017.

Constantin’s EU trade mark application for ‘Fack Ju Göhte’ was initially refused by the EU Intellectual Property Office (“EUIPO”). They considered the mark applied for to be contrary to ‘accepted principles of morality’. This was on the basis that the relevant German-speaking public would recognise the English expression ‘fuck you’ in the first part of the trade mark, a phrase which the EUIPO considered to be vulgar and offensive. The addition of the word ‘Göhte’ did not do enough to remove the vulgarity, nor did the success of the film and fact that members of the German speaking public would either have seen or heard of the comedy – which Constantin argued meant that they would not view it as shocking.

Unhappy with the decision to refuse their trade mark, Constantin appealed the matter all the way up to the CJEU, where it was held that the relevant test to apply was whether the relevant public, being reasonable people with average thresholds of sensitivity and tolerance, would perceive the sign/brand as being contrary to fundamental moral values or standards of society as at the date the application was filed. Given the comedies’ well known status, the perception of the relevant public and the way in which it had reacted to the ‘Fack Ju Göhte’ films,at launch and up until the filing date, was also relevant. It was notable, therefore, that whilst the success of the films was not conclusive of the social acceptance of its title, it was at least indicative of such acceptance, particularly as the title did not appear to provoke any controversy among the audience. The comedies had also been approved for viewing by young people in schools. As a result, the CJEU held that the English phrase ‘fuck you’ did not have the same impact on the German speaking public as it would elsewhere – even if they would understand the phrase – and the EU trade mark application for ‘Fack Ju Göhte’ was accepted for registration.

This case highlights the difficulty of assessing morality in the EU. It also shows that the EUIPO and the European courts still have difficulty agreeing on what is and isn’t morally acceptable – much like society as a whole. As the gate keepers to granting monopolies to signs/brands, it may be seen as right and logical for the Intellectual Property Offices around the world to interpret these provisions broadly. However, as opined by Advocate General Bobek in his Opinion on the ‘Fack Ju Göhte‘ case, it must be recalled that the protection of public policy and morality is not the primary aim of Intellectual Property Offices, and this ground for refusal is perhaps better viewed as a “safety net” setting limits to the pursuit of other aims.

‘Fack Ju Göhte’ serves as a reminder to brand owners to conduct clearance searches prior to filing trade mark applications, to identify the potential for objections to be raised early on. In this case, however, the comedy had already been actively using their name, so a change of brand may have not been appropriate, although a search is likely to have flagged the potential objections. This in turn could have led to Constantin considering national trade mark registrations, for example only in Germany and Austria where the comedies are so well known and the meaning of the English ‘fuck you’ less relevant to the average consumer, thereby avoiding its hard-fought battle for EU-wide protection.

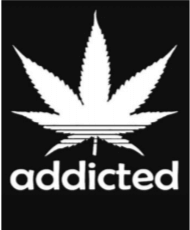

The issue of morality and public policy was also considered fairly recently in a UK trade mark registration for the ‘Addicted’ device mark (below) which was invalidated, inter alia, on the grounds of public policy and morality (Case O/442/19, Addicted Original Ltd v Adidas AG, invalidity number 502260, 30 July 2019).

After Addicted Original Ltd had secured registration for the above mark, Adidas AG (“Adidas”) filed an invalidity action against the registration. In that case, the UKIPO found that “an identifiable significant section of the public” would recognise the ‘Addicted’ mark as including a representation of a marijuana leaf. To those members of the public, the trade mark conveyed a clear message relating to addiction to illegal drugs. Allowing registration would therefore have undermined principles of accepted social values.

The owner of the ‘Addicted’ brand argued that the registration should be accepted as they were involved with the movement to legalise cannabis for medical purposes. This argument was given little weight by the UKIPO’s hearing officer since, not only was cannabis not legalised in the UK, but the word ADDICTED in the trade mark “goes beyond the suggestion of recreational or medical use of the drug but to a social issue of dependency upon drugs“. It is also well established that, for the purposes of assessing morality, whether the goods/services of interest can or cannot be legally purchased in the country where trade mark protection is filed is not relevant.

As mentioned above, the ‘Addicted’ mark was allowed to proceed to registration by the UKIPO before it was challenged by Adidas for invalidity. This is interesting since the registration was subsequently removed from the register on moral grounds. Whilst this may be an indication that the UKIPO is placing a lower threshold on morality and public policy than the EUIPO, it does serve as a reminder for brand owners to consider their strategy when it comes to monitoring the trade mark registers for brands of concern.

In addition to careful monitoring, brand owners should contemplate the types of objections that could be encountered when developing their brands and consider how best to protect potentially provocative or controversial marks. We would be happy to assist any brand owner seeking to develop their brand protection strategy.