Battle of the supermarkets: Lidl prevail at Court of Appeal over Tesco’s use of Clubcard logo

The high profile dispute between supermarket retailers Lidl and Tesco has now come to a head at the Court of Appeal, with Lidl emerging as the winner.

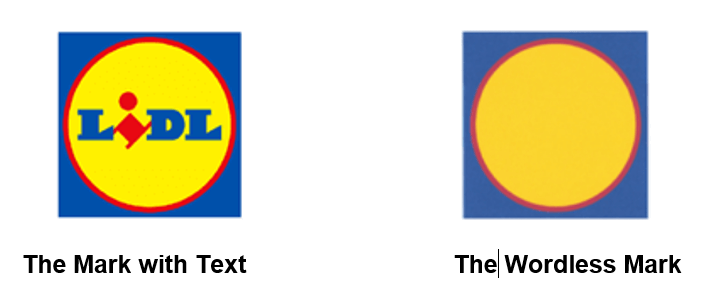

The dispute related to Tesco’s adoption in 2020 and subsequent use of its Clubcard Prices logo for its discount price scheme, which Lidl claimed infringed a number of its IP rights in the well known Lidl logo. Lidl’s logo was protected as a trade mark in two different forms, as shown below:

An example of Tesco’s Clubcard Prices logo (referred to in the judgment as the “CCP Signs”) is shown below.

High Court ruling

In April 2023, Judge Joanna Smith found in Lidl’s favour on its claims that Tesco’s use of the CCP Signs infringed Lidl’s trade marks (under Section 10(3) Trade Marks Act 1994) and amounted to passing off. She also found that the CCP Signs had been copied from the Lidl logo, thereby also infringing Lidl’s copyright. The trial judge also held that Lidl’s Wordless Mark was distinctive of Lidl (based on a YouGov survey in which 75% of respondents seeing the Wordless Mark identified it as being the Lidl logo) and that it had been used by Lidl (in the form of the Mark with Text).

Notwithstanding these findings, the trial judge also held that certain of Lidl’s historic trade mark registrations for its Wordless Mark were filed in bad faith because Lidl had failed to evidence its good faith intentions to use the marks at the time of their filings. (However, this did not impact the overall outcome of the case given that infringement was found in relation to the Mark with Text).

For the High Court judgment see: Lidl Great Britain Ltd & Anor v Tesco Stores Ltd & Anor [2023] EWHC 873 (Ch) (19 April 2023) (bailii.org).

Both sides appealed, with the appeals heard by Arnold, Lewison and Birss LLJ between 19-21 February 2024.

On 19 March 2024, the Court of Appeal handed down its judgment.

Tesco’s appeal against the findings of trade mark infringement and passing off

The Court of Appeal upheld the findings of trade mark infringement and passing off.

Arnold LJ, giving a lengthy lead judgment, described the High Court judgment as being “an impressively careful and detailed analysis of the issues, evidence and argument”. He reiterated the role of the appellate court: in so far as an appeal challenges findings of fact, the appellate court is only entitled to intervene if those findings are rationally insupportable. In so far as the appeal challenges a multi-factorial evaluation, the appellate court is only entitled to intervene if the trial judge erred in law or principle.

Consumer evidence

As to trade mark infringement and passing off, Tesco’s main grounds for challenging the trial judgment were the trial judge’s treatment of certain of the evidence before her. Arnold LJ took the opportunity to review the various types of evidence which often appear in trade mark cases, the proper role they should have and the potential pitfalls of each, looking at survey evidence, expert evidence, trade evidence and consumer evidence (e.g. evidence of actual confusion).

In this case, the trial judge had been asked to consider, amongst other things, a range of consumer evidence, including various consumer reactions to seeing the CCP Signs. With regard to consumer evidence, Arnold LJ explained that unless there was reason to think that the consumers in question were idiosyncratic (i.e. outliers of some sort), then it may be of assistance to the court, but the judge must evaluate such evidence with caution and must not treat it as determinative of the issue which fell to the court to decide. Subject to those caveats, the court may give such evidence whatever weight the court considers appropriate in the circumstances of the case.

Arnold LJ noted that the price matching allegation (i.e. that the CCP Signs conveyed the message that Tesco’s Clubcard prices were the same or lower than Lidl’s) underpinned the trial judge’s findings of both unfair advantage (for trade mark infringement) and misrepresentation (for passing off).

Arnold LJ proceeded to review the three main strands of evidence considered by the trial judge (in the context of the passing off analysis) in reaching her conclusion about the price matching allegation:

- the two consumer witnesses who gave evidence at trial of their reaction to seeing the CCP Signs;

- the Vox Populi of other consumer reactions encountering the CCP Signs; and

- a market research survey commissioned by Tesco to gauge spontaneous reactions from consumers seeing the CCP Signs for the first time.

The trial judge took the view that this evidence all supported her conclusion that a price matching message was being conveyed by the CCP Signs. Arnold LJ concluded that the trial judge had evaluated each piece of evidence with care and without treating any one piece of evidence as determinative of any issue which the court had to decide. She was therefore entitled to reach the view that the CCP Signs conveyed the price matching message to the average consumer based on the evidence before her.

In concluding, Arnold LJ said that whilst, at first sight, he had found the trial judge’s conclusion that the price matching message was being conveyed as somewhat surprising, it became less surprising given the findings that the Wordless Mark had become distinctive of Lidl, the CCP Signs called the Lidl logo to mind and that Lidl had an accepted reputation for low prices.

Detriment

Whilst Lidl’s trade mark infringement case succeeded on the basis of unfair advantage alone, Arnold LJ went on to consider whether it should also succeed on the basis of detriment as well. Here too, he was satisfied that the trial judge was entitled to conclude from the evidence that there was the necessary change in economic behaviour for detriment to be established.

This was based on (i) Tesco’s Clubcard campaign having slowed the switching from Tesco to Lidl; and (ii) Lidl having engaged in corrective advertising to counter the problem being caused by the CCP Signs.

Judgments of Birss and Lewison LLJ

Birss and Lewison LLJ also upheld the findings of trade mark infringement and passing off, although Lewison noted that he had found them to be “very difficult, at the outer boundaries of trade mark protection and passing off”.

There was some discussion as to the proper assessment of “due cause” in the context of Section 10(3). Was this to be assessed sequentially only after unfair advantage or detriment had been found? Lewison and Birss LLJ doubted such an approach could be correct because this would seemingly make it possible for the defendant to be found to have taken unfair advantage, yet nonetheless have done so with due cause, an apparent contradiction in terms. Ultimately, the court did not consider the outcome of this appeal turned on this issue.

Lidl’s appeal against the findings of bad faith of the Wordless Mark registrations

At trial, the trial judge had found that Lidl’s trade mark registrations for its Wordless Mark from 1995, 2002, 2005 and 2007 should be revoked for bad faith. This was despite also having found that the Wordless Mark was distinctive of Lidl and Lidl was using the mark. Lidl appealed.

The Court of Appeal held that the circumstances in which these marks were filed gave rise to a prima facie indication of bad faith because:

- Lidl had never used the Wordless Mark in the form registered;

- it was to be inferred that Lidl had not intended to use the Wordless Mark in the form registered;

- if Lidl was right that use of the Mark with Text amounted to use of the Wordless Mark, it did not need to register the Wordless Mark unless the purpose was to give Lidl wider or different protection; and

- it was to be inferred that the application to register the Wordless Mark was made solely for the purposes of using it as a legal weapon and not in accordance with its function of indicating origin.

In such circumstances, the evidential burden shifted to Lidl to explain its intentions when making these applications. The Court of Appeal agreed with the trial judge that Lidl had been unable to prove that, at the time of filing each of these marks, it had the necessary intention to use the mark or that the mark had the necessary reputation. Consequently, the Court of Appeal concluded that the trial judge had considered the available evidence from Lidl carefully and was entitled to reach the conclusion that Lidl had not discharged the burden of proving good faith.

Lidl’s appeal was therefore dismissed.

Tesco’s appeal against copyright infringement

At trial, the trial judge had held that copyright subsisted in the Mark with Text as an original artistic work, and that a substantial part of that work had been copied by Tesco’s design agency in creating the CCP Signs. Indeed, in the trial judgment, the trial judge has been highly critical of Tesco’s evidence on the how the CCP Signs was created, finding the evidence to be inaccurate, misleading and designed to obscure key aspects of what actually happened.

Whilst Tesco’s appeal did not challenge the trial judge’s findings on either subsistence or copying, Tesco challenged whether a ‘substantial part’ of the work had been taken, an argument which had not been fully advanced before the trial judge. The Court of Appeal upheld Tesco’s appeal in this regard: the scope of protection afforded to the work was narrow and, by using a slightly different shade of blue and distance between the circle and the square, what Tesco had copied did not amount to a substantial part of the work.

Comment

At around 100 pages, the trial judgment in this case was, to use Arnold LJ’s words, an impressively careful and detailed analysis of the issues, evidence and arguments. It is a well established principle that absent any obvious error in law or principle, or rationally insupportable conclusion, the Court of Appeal should not interfere with the findings of the trial judge. As Lewison LJ noted in Fage UK Ltd v Chobani Ltd “In making his decisions the trial judge will have regard to the whole of the sea of evidence presented to him, whereas an appellate court will only be island hopping.”

And so it was here. With the exception of one argument with regard to copyright infringement (which was not pressed before the trial judge), the Court of Appeal has left the trial judgment largely undisturbed.

Having succeeded on trade mark infringement and passing off, Lidl emerges as the clear winner. It will now benefit from an injunction against Tesco’s use of the CCP Signs and, given Tesco’s extensive use of the CCP Signs over a period of 4 years, likely a very substantial damages award.

This case was far from straightforward for Lidl however. Unlike most trade mark cases, which normally turn on whether there is a likelihood of confusion between the claimant’s mark and the defendant’s sign under Section 10(2) (Trade Marks Act 1994), Lidl was never suggesting that consumers were confused as between Tesco and Lidl (although some evidence origin confusion did emerge). Rather, Lidl’s case was brought only on the basis of Section 10(3), requiring it to show that Tesco’ CCP Sign conveyed a false price matching message to some consumers and/or caused some other change in economic behaviour.

Lidl was ultimately successful in satisfying the demanding hurdles of Section 10(3). This was due to the comprehensive evidence that Lidl was able to show the trial judge to allow her to understand the real life effects of Tesco’s use of the CCP Signs in the unique environment of supermarkets battling to win and retain customers.

Bird & Bird acted for Lidl in this case. The team was led by IP partner, Ewan Grist, supported by solicitor-advocate Tristan Sherliker, partner Emma Green and associates Bryony Gold and Sam Peterson.