Brick Wars Episode VIII – The Last IP

LEGO has built a strong market position over the past decades. This is not only due to the quality of their products, but also due to their ability to keep the competition at arm’s length. In parts of Europe, for example, LEGO has developed a monopoly-like position in the market for “clip bricks” and defends this with almost all the weapons in the arsenal of IP protection. This is an interesting example of how different IP rights can be used together or gradually – and also what limitations different IP rights have.

Originally, LEGO bricks were protected by patents for the technical solution that holds the bricks together. In other words, the durability of the individual bricks and the clip solution that enables the entire system of compatible LEGO bricks to hold together. Due to the fixed term nature of patents, once it expired, the bricks and the technical solution of the “clip bricks”, in theory, became available for the public to reproduce.

When other suppliers subsequently wanted to bring compatible bricks onto the market, LEGO initially defended itself very successfully using, among other things, unfair competition law in Germany. Under the heading of “insertion into another’s series” (a German variant of “passing off”), competitors were prohibited from producing bricks that were compatible in size with LEGO, because this exploited LEGO’s established competitive advantage and market position. It was not until much later that the German courts recognised that the competitive position LEGO sought to defend stemmed from its monopoly of patent protection and therefore should not be allowed to endure through unfair competition law.

LEGO then tried trade mark law, and in particular applied for the central and iconic “2×4” brick as a three-dimensional trade mark. This allowed them to prohibit all other suppliers of compatible bricks from using the iconic “2×4” brick. Since that brick is central to many models and there was also the possibility that the trade mark’s scope of protection extended to similar shapes, this again severely restricted other suppliers. Suppliers in competition with LEGO therefore lobbied for cancellation of the trade mark and were eventually successful.

Since then, third-party suppliers have been on the rise in Europe. LEGO now has only design rights and copyright in its arsenal, and only very limited trade mark rights. Designs can be used to protect aesthetic achievements. The prerequisite for this is that the product is “new” and has “individual character”. This means that the exact product must not have been made known to the public before, and it must stand out from the “previously known set of forms”. However, this is not examined during registration. That is why design registrations are easy to obtain. Whether the registration is valuable, however, only becomes apparent when it is enforced. LEGO has design rights in some of its newer and more unusual bricks, as well as in some of the minifigures in the LEGO Friends series.

Copyright protects intellectual achievement in works of art, literature or architecture. This also extends to the design of clamp building block sets and to the building instructions. LEGO is taking action – rightly and vehemently – against suppliers of plagiarised products who copy individual sets almost identically and sometimes even copy the building instructions. To stop this, LEGO obtained several judgments in China against the company LEPIN in recent years and even enforced the destruction of one of their factories in 2019 as LEPIN had produced particularly brazen copies of existing LEGO sets on a large scale and offered them at a lower price.

However, where third-party suppliers avoid LEGO’s (few) design-protected bricks and put their own sets on the market, there are no legal objections (anymore). According to industry portals, the quality of clip bricks from competitors is constantly improving, while LEGO sometimes struggles with quality problems, which could have an impact on its market position.

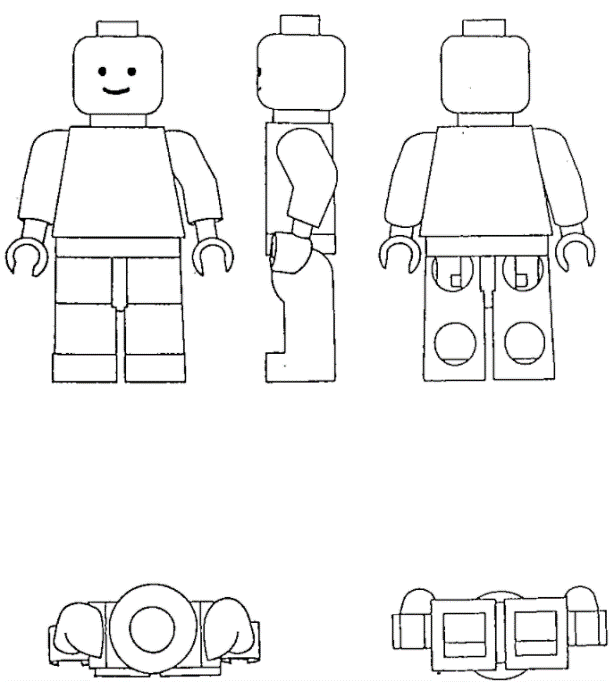

However, LEGO still has its 3D EUTM protection in its minifigure (Reg. No. 000050450).

LEGO has enforced the rights in this trade mark extensively and is currently taking action against all suppliers (and their importers) who offer even remotely similar minifigures.

In Germany, LEGO has succeeded in obtaining several preliminary injunctions against importers of similar minifigures. As a result, these importers are no longer allowed to sell entire brick sets where they contain the minifigures in question. As a solution, some importers are selling the sets without minifigures as well as trying to cancel LEGO’s 3D EUTM for the minifigure.

The manufacturers and importers affected by the current warning letters argue that LEGO is ultimately trying to monopolise the idea of a minifigure matching the bricks. For example, the manufacturers and importers argue that a minifigure’s “hand” is designed to hold accessories that are not, and cannot be, protected by IP rights and so the same argument applies to the minifigure’s “feet” and their connections that allow the figures to stand or sit on studs. If these – technically conditioned – details were removed, a figure only remotely reminiscent of a human being would remain, which could not be covered by trade mark protection. Finally, the range of different figures that LEGO is currently attacking shows that the company seeks a broad scope of protection.

LEGO’s current warnings have been heavily criticised on social media because, among other reasons, wide-reaching influencers were also affected (including “Held der Steine” Thomas Panke, Germany’s most influential YouTuber for clip bricks).The matter will undoubtedly drag on for some time – so watch out for further episodes in this saga.