Can emojis be trade marks? Thumbs down from EUIPO leaves applicant with sad face

In Case R 2305/2022 Käselow Holding GmbH (1 June 2023), the EUIPO Board of Appeal (BoA) rejected an appeal against the refusal to register a sign commonly recognised as the emoji for “I love you” as an EU trade mark (“EUTM”) in Class 36 (real estate and financial services) and Class 37 (construction and building cleaning services) on the basis that the mark lacked distinctive character.

Emojis

Where would today’s world find itself without the humble emoji? Also popularly known as emoticons, ‘emojis’ are pictograms used in mobile and electronic interactions, to convey the sender’s emotions in ways that plain text just can’t.

Having first been introduced in the late 1990s on Japanese mobile phones, emojis gained global notoriety in the 2010s after being rolled out on many popular mobile phone operating systems – such that today, emojis can be said to enjoy worldwide ubiquity.

Relevant law

Under Article 7(1)(b) of the EU Trade Mark Regulation 2017 (EUTMR), an EUTM application can be refused on the ground that the trade mark is devoid of any distinctive character.

Following established EU case law principles, distinctive character is assessed in relation to the goods or services for which protection is sought, and the perception of the relevant public, who are taken to perceive the mark as a whole (i.e., without analysing its various details).

Facts

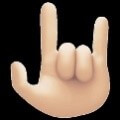

In December 2021, Käselow Holding GmbH (the applicant), applied to register the following sign as an EUTM:

The sign is internationally recognised, including in sign languages and on emoji keyboards, as depicting the gesture for “I love you”.

The applicant sought registration of the sign for services in Class 36 (real estate and financial services) and Class 37 (construction and building cleaning services).

In November 2022, the EUIPO Examiner refused registration of the sign as lacking distinctive character under Article 7(1)(b) EUTMR. The applicant appealed.

Decision

Rejecting the appeal, the BoA ruled that:

- The sign was a realistic and common illustration of the “I love you” gesture and was a pictogram or emoji with a clear and specific message.

- Any submitted differences between the sign applied for and the “I love you” emoji, such as the fact that the gesture in the sign was on the left hand, and that the proportions and colour of the hand weren’t the same, were sufficiently common and existing variants of the emoji. These variations were not decisive to the underlying gesture. They were not sufficiently distinctive features to a member of the public who perceived the mark as a whole and not its various details, and who would have an incomplete recollection of the sign.

- Generally, the main function of emojis was as a “parallel language”, conveying a nuanced meaning and making it easier to express feelings. Therefore, “as a rule, they are not perceived as an indication of origin”.

- The average consumer was assumed to be accustomed to many pictograms representing emotions (such as emojis), which were to be perceived as a general advertising message, or purely decorative elements, that were devoid of any distinctive character. These pictograms also lacked distinctiveness as they were simple geometric shapes, design elements customary in advertising, stylised instructions on the use of the product or the reproduction of the product itself.

- Customers of services in Classes 36 and 37 would perceive the sign as a general advertising message indicating that they would be particularly satisfied with the services offered under the sign, and would think of them “on account of their satisfaction with loved affection”. The consumer would merely infer from the sign a generalised positive connotation (such as an attractive decoration, a general laudatory statement and incitement to purchase). As a simple representation of a positive gesture, the sign did not contain anything capable of distinguishing the origin of those services.

Comment

Of the various challenges involving emojis and trade marks, this case demonstrated one particular problem – the problem of showing distinctiveness in the traditional ‘emotional’ emojis.

This type of emoji is so commonly used that any attempt to claim exclusive rights in it is unlikely to be successful.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, in order to successfully obtain a registration, such a sign must be sufficiently distinctive. And this case shows that nit-picking over minor nuances is not enough – prospective applicants must demonstrate salient departures from the standard emoji in question.

The problem is, there’s only so many ways to significantly re-depict an ‘emotional’ emoji like this – take your mark too far away from the original and, while it may be distinctive, the emoji is unlikely to be recognised or understood by the consumer. That might defeat the purpose.

With that said, emojis can be – and indeed have been – registered as trade marks. This has become possible in large part due to the fact that emoji libraries have now been so heavily expanded, such that they illustrate more than just emotions and gestures – such as food, plants, animals, activities, objects, and travel.

Those kinds of emojis can be redrawn in loads of different and distinctive ways. Although other challenges remain (not least enforcement problems), at least these kinds of emoji are more capable of overcoming the specific hurdle of distinctiveness, while staying sufficiently true to the emoji form.