EUIPO Board of Appeal invalidates 3D Rubik’s cube mark

- Verdes sought to invalidate a 3D mark including colour claims for the Rubik’s cube

- The Board of Appeal agreed with the Cancellation Division that the mark was invalid as it consisted exclusively of the shape of goods necessary to obtain a technical result

- The absence of ‘shape’ per se does not exclude colours from obtaining a technical result

On 20 October 2023 the First Board of Appeal of the EUIPO issued its decision in Spin Master Toys UK Limited v Verdes Innovations SA (R 850/2022-1). The Board of Appeal upheld the Cancellation Division’s decision that Spin Master’s three dimensional (3D) shape mark for the Rubik’s cube had been registered contrary to Article 7(1)(e)(ii) of Regulation 207/2009.

Background

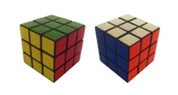

On 9 January 2008 Seven Towns Ltd, the original proprietor of the contested mark, applied for a 3D mark including colour claims in Class 28:

In 2013 Verdes led an application for a declaration of invalidity of the mark based on Articles 7(1)(a), (b), (c) and (e) of the regulation. The proceedings were suspended until 2021, pending ongoing proceedings relating to an earlier registration by Seven Towns for a 3D colourless Rubik’s cube mark, applied for in 1996. The current proceedings were resumed following an ending of invalidity by the Court of Justice of the European Union for the 1996 mark, due to it infringing Article 7(1)(e)(ii).

On 25 March 2022 the Cancellation Division similarly declared the 2008 mark invalid on the basis of Article 7(1)(e)(ii). Spin Master appealed to the Board of Appeal.

Decision

Article 7(1)(e)(ii) prohibits the registration of a sign which consists exclusively of the shape of goods incorporating essential characteristics necessary to obtain a technical result. Under Article 52(1)(a), any mark registered in breach of Article 7(1)(e)(ii) shall be declared invalid. The Board of Appeal recalled that the provision aims to promote fair competition by preventing proprietors from obtaining potentially perpetual monopoly rights for technical or functional features of a product.

Due to the registration date of the contested mark, its validity was determined in relation to Regulation 207/2009, not the more recent Regulation 2017/1001, which added “or another characteristic” to features that will be excluded if necessary to obtain a technical result. The board recounted the following points on Article 7(1)(e)(ii):

- The ability of alternative shapes to achieve the same technical result does not prevent a mark from being invalidated.

- ‘Essential characteristics’ refer to the most important elements of the sign.

- ‘Essential characteristics’ must be assessed in light of the technical function of the actual goods and also take into account previous patents that outline the functional elements of the shape of the goods.

The 1996 colourless mark

It was common ground between the parties that the 1996 and 2008 marks represented the same object, although their scope differed due to the addition of colour claims in the 2008 application. Consequently, the Board of Appeal relied on two ‘essential characteristics’ necessary to achieve a technical result that it had previously identi ed to invalidate the 1996 mark:

- the cube shape of the toy, which allows the 3×3 squares on the faces of the Rubik’s cube to be rotated vertically and horizontally to solve the Rubik’s cube; and

- the black grid structure, which creates the physical separation on the faces of the cube to allow the 3×3 squares to be rotated.

This left the contrasting colours on the cube faces as the only remaining essential feature for the board to determine the technical necessity of. This is what the majority of the board’s decision focused on.

The technical function of the colours

- The board rejected Spin Master’s argument that, although the contrasting colours on the 3×3 squares are an essential characteristic, they could not be considered a ‘shape’. The board held that the absence of ‘shape’ per se does not exclude colours from obtaining a technical result. To hold otherwise would allow proprietors to avoid the functionality exclusion by merely adding colour to functional elements of a shape.

- The board distinguished the issue here from Louboutin (C-163/16) and Textilis (C-21/18), as those decisions concerned colours per se and 2D position marks, whereas the contested mark is a shape mark which incorporates colour.

- The board rejected Spin Master’s argument that use of colour was not the only solution to obtain a technical result (Spin Master argued that, for example, symbols could be used to distinguish the 3×3 squares), as this argument suggested that the colours on the squares were separate from the shape itself.

- The essential element that was necessary was any combination of contrasting colours, not just the colours represented on the register.

- Any copyright or design protection that existed for the colour combination was not relevant to its distinctiveness and certainly could not exclude the application of Article 7(1)(e)(ii).

Scope of goods

Spin Master also contested the scope of goods the Cancellation Division had determined the essential characteristics were necessary for.

- The Cancellation Division had held that “three-dimensional puzzles”, for which the essential characteristics were necessary, encompassed “toys, games, playthings and jigsaw puzzles, three-dimensional puzzles; electronic games; hand-held electronic games” – the entire goods speci cation the mark had been applied for.

- Spin Master contested the inclusion of “jigsaw puzzles”, as the individual squares on the Rubik’s cube could not achieve the technical result of being pressed together into position like a traditional puzzle.

- The board upheld the inclusion of jigsaw puzzles as there was nothing in the representation of the sign to exclude the possibility that a user may dismantle and reassemble the squares on each face of the Rubik’s cube to achieve the goal of the toy.

Comment

This decision reinforces that 3D marks remain very difficult to successfully register and defend. The judgment demonstrates the EUIPO’s tough approach towards any characteristic that is necessary to obtain a technical result, even for signs registered prior to Regulation 2017/1001. It is clear from the judgment that the EUIPO will apply a post-Regulation 2017/1001 approach to signs registered before the 2017 regulation. The decision also demonstrates the board’s broad interpretation of the scope of goods for which any essential characteristics are deemed necessary to obtain a technical function.

This article first appeared in WTR Daily, part of World Trademark Review, in December 2023. For further information, please go to www.worldtrademarkreview.com.