Not my style to infringe your trade mark – the Australian Federal Court considers the legal risks of using a trade mark as a style name

When you hear the brand name “Hermes”, chances are you will automatically think of the “Birkin”, “Constance” or “Kelly” handbags.

And what about shades of red lipstick? Dolce & Gabbana’s “Devil”, MAC Cosmetic’s “Ruby Woo” and Dior’s iconic “999” may come to mind.

Style names are not only ubiquitous in the fashion and beauty industries but are also a helpful way to identify different products. But do style names pose the same legal risks as brand names or sub-brand names? Should businesses be more vigilant in selecting style names and conduct trade mark searches before launching a product?

A recent decision of the Federal Court of Australia provides some lessons for businesses in selecting and using style names.

Background

In Pinnacle Runway Pty Ltd v Triangl Limited [2019] FCA 1662 (Judgment), Justice Murphy dismissed allegations of trade mark infringement that were brought against a company that had used another company’s registered trade mark as a product style name.

Pinnacle is a designer and manufacturer of a range of women’s clothing including swimsuits (the DELPHINE Products). Pinnacle is the owner of the registered trade mark “DELPHINE” for clothing, headwear and swimwear (the DELPHINE Trade Mark). Pinnacle promoted the DELPHINE Products in print and online, including on blogs and via Instagram influencers, and sold the DELPHINE Products through popular online fashion retailer The Iconic.

The respondents in the proceeding, Triangl also designed and manufactured women’s clothing but operated an online store focusing on swimwear. A Triangl entity is the owner of a number of registered trade marks, including TRIANGL (the TRIANGL Trade Mark).

Pinnacle sent a letter of demand to Triangl alleging that in selling a range of swimwear online by reference to the name DELPHINE it was infringing the DELPHINE Trade Mark. Although Triangl did not initially agree to cease using DELPHINE, it subsequently agreed to cease use and issue an apology if Pinnacle agreed to forego its claim for compensation. Notwithstanding Triangl’s concessions, Pinnacle commenced proceedings in the Federal Court of Australia.

Are style names “use as a trade mark”?

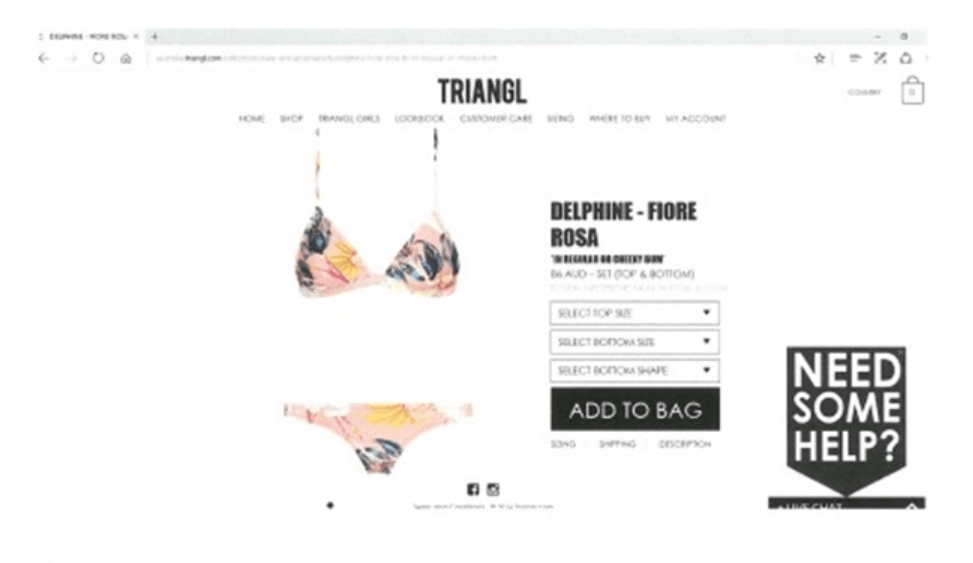

Triangl admitted that for 6 weeks it had marketed and sold a bikini with the style name “Delphine” in three different floral designs and these products were promoted under the TRIANGL Trade Mark. It denied using DELPHINE “as a trade mark”, arguing that the TRIANGL Trade Mark distinguished its products from those of other traders and the name DELPHINE was only used to assist consumers differentiate between bikini styles on its website. A screenshot of one of the DELPHINE-style products as it appeared on the Triangl website is shown below:

Triangl put on evidence (including expert evidence) about the widespread industry practice in women’s fashion of using style names – which were often women’s names. Further, Triangl submitted that due to the rapid turnover of stock and repeated use of the same colours in women’s fashion, referring to a product by style name is easier than a number for both consumers and retailers, for example, in processing complaints and for stock-keeping activities. It argued that consumers were used to this practice and were unlikely to perceive the name DELPHINE as a trade mark, i.e. to distinguish Triangl’s goods from those of other traders. Triangl’s position was accepted by the Court.

One of Pinnacle’s submissions was that DELPHINE is an unusual name and is therefore so distinctive and memorable to consumers that they would perceive Triangl’s use of the name as a sub-brand. This submission was not accepted by the Court, having regard to the familiarity of consumers to the practice described above in addition to evidence that style names did not have any intrinsic value to fashion retailers compared to head brands (which in this case, both parties had registered as trade marks). His Honour also observed that it was unlikely that Triangl’s 35 style names were all intended to be sub-brands of Triangl.

The pitfalls of litigation

While the enforcement of trade marks and other intellectual property rights is important in any brand strategy, the first line of the Judgment serves as an acute warning to prospective litigants and their advisors: “These are ill–advised proceedings in respect of alleged trade mark infringement and cancellation of a trade mark, and there is no clear winner.”

At the time it commenced proceedings, Pinnacle was a relatively “young” company: it was incorporated in 2014 and it launched the DELPHINE brand the following year. In circumstances where:

- the period of alleged trade mark infringement was only 6 weeks;

- the alleged infringing use ceased within 3 weeks of Pinnacle’s letter of demand;

- Triangl had agreed to desist from the allegedly infringing use before the proceeding was filed;

- Triangl’s total revenue through the alleged infringing conduct was less than $40,000; and

- Pinnacle was unable to show that it had lost any sales,

Practical implications

Like most industries, the fashion and beauty industries demand innovation. However, that demand is amplified in fashion businesses, with high product turnover and new styles being introduced on a seasonal basis. It is relatively rare that a particular style becomes so successful that it develops its own reputation.

This decision provides some comfort to businesses that use style names (but importantly, every case turns on its facts) and also serves as a cautionary tale to parties to carefully consider their enforcement strategy. Some key takeaways are that:

- Use of well-known brands and trade marks as style names, particularly where the goods or services involved are the same or similar, should be avoided. There are circumstances where using a brand as a style name can amount to trade mark infringement, misleading or deceptive conduct or passing off.

- Using a style name in conjunction with one’s own registered trade mark, or some other distinctive trade indicia may but will not necessarily be a defence to trade mark infringement. The overriding consideration is whether there is a clear dominant “brand” on the packaging or advertising material in question and its effect on the balance of the material.

- If businesses are concerned about their branding strategy and whether their use of style names could infringe third party rights, advice should be sought.

- Litigation is never without risk. Companies – particularly young companies that have not had time to establish a significant reputation or cannot show direct losses of sales from contraventions – should carefully consider the commercial realities of enforcing their trade marks before assuming the risk. Also where concessions have been made serious thought should be given before proceeding with litigation.